Frances Bingham

Sylvia Townsend Warner described her lover Valentine Ackland as ‘a lovely, mysterious, enchanted creature’. She found Valentine’s striking appearance and unpredictable character an endless source of fascination and inspiration. But, central as she is to Sylvia’s story, Valentine remains in some ways a mystery.

She was born in London on 20 May 1906 at 54 Brook Street, an imposing house in Mayfair where her father had a lucrative private dental practice. She was named Mary Kathleen Macrory, but as a child she was always called Molly. Her father, Robert, was awarded a CBE for pioneering facial reconstructive surgery during the First World War, but despite his professional success he was a melancholic, violent-tempered man, feared by his family. Her mother, Ruth, took refuge in hypochondria and pious sentimentality to console herself. Molly’s sister, Joan, was eight years older and deeply resented her younger sibling. Joan’s relentless abuse, and her parents’ neglect, made Molly’s childhood miserable rather than privileged.

Sensitive Molly was damaged by this harsh upbringing; she became shy, painfully self-conscious, obsessed with death and with her own lack of heroism. But when they holidayed at the family home in Winterton on the Norfolk coast, Molly ran wild in the country and was ecstatically happy. There Robert taught her to drive, row, shoot, fish, even box (perhaps as a surrogate son). Her other sanctuary was reading, especially poetry; an escape into the world of imagination.

Destined to be a debutante, Molly was sent to finishing school in Paris in 1922. There she fell in love with a fellow-student, Lana. When Joan betrayed them to Robert, he threatened to disown his once-favourite daughter. With a stubborn courage which enraged him, Molly refused to admit that their love was unnatural or wrong. ‘He did not know I had the poets to protect me,’ she wrote. Molly was sent away in disgrace to a domestic training college in Eastbourne where she was miserable, developed anorexia, and ran away. When Robert died not long after, they were unreconciled; Valentine knew her father had recognised that ‘what he hated was an essential part of me.’

Still only seventeen and at home again, Molly met a new lover, Bo Foster, who was older and more worldly. She completed Molly’s education both culturally and sexually and encouraged her poetic ambitions. Molly was now a ‘smart, devil-may-care young woman’ with polished manners and a taste for dancing and drinking. She was also a romantic, longing for a great love which discreet Bo dared not offer, so their relationship remained secret.

Desperate to escape from her family, at nineteen Molly impulsively married Richard Turpin, a handsome homosexual who hoped to change his sexuality. But their honeymoon was a disaster of sexual incompatibility and mutual embarrassment. They divorced and, as recent Catholic converts, applied for annulment of the unconsummated marriage.

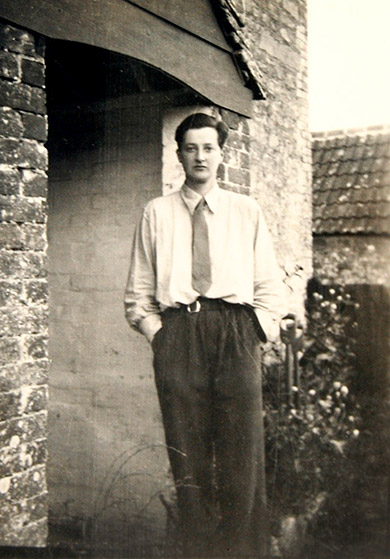

Over the next few years Molly Turpin reinvented herself; she took rooms in Bloomsbury, modelled for Eric Gill and Augustus John, had experimental love-affairs. She was briefly pregnant, but miscarried, to her regret. After she was twenty-one, it was always women: Dorothy Warren, Anna May Wong, Nancy Cunard. She chose the androgynous name Valentine Ackland to describe this new self, invoking the patron saint of lovers and reclaiming her father’s name. And she declared her new independence by putting on trousers – ‘unheard of then except among perverts’ – as a symbol of her masculine freedom and potency. Valentine was famous for cross-dressing all her life but, though she did not identify as a woman, she did call herself a ‘Lesbian.’ Her gender identity seems closer to butch, non-binary or non-gender-conformist than trans, in contemporary terms.

Valentine often stayed in the Dorset village of Chaldon, where she met Sylvia Townsend Warner, a celebrity after her recent best-seller Lolly Willowes (1926). Sylvia was twelve years older, erudite, blazingly talented and socially alarming; Valentine alleged she was ‘rude’ at their first encounter, perhaps disconcerted by the scented and urbane youth in trousers. But as well as admiring Valentine’s long legs and Eton-cropped hair, Sylvia recognised her poems as ‘the genuine article.’ A flirtatious friendship developed; Sylvia proposed that they could share ‘Miss Green’, her newly-bought cottage in Chaldon; Valentine accepted. ‘I have good hopes,’ Valentine wrote in her diary, while Sylvia recalled ‘wooing her with every word.’ In October 1930 they began the passionate love-affair which would obsess them both for the rest of their lives.

Valentine had found the great love she desired, the woman who would give her ‘everything, without any possible reservation’. Ever after they celebrated 12 January – the day in 1931 when they spontaneously exchanged vows – as a wedding anniversary. The love-poems they wrote to one other were published in Whether a Dove or Seagull, in 1934; Valentine unrealistically believed that the joint book would establish her poetic reputation. It was well-reviewed, but its bland reception was a bitter disappointment to her.

From 1933-4 Valentine and Sylvia lived at Frankfort Manor in Norfolk, a beautiful dilapidated seventeenth century house, ‘in a kind of solemn, fairy tale splendour’, later remembered as an idyllic time. But it ended when they were sued for libel (after merely signing a petition against the ill-treatment of young women in a Chaldon institution), with high legal costs. They returned to a cheap, isolated cottage on the downs above West Chaldon.

Sylvia always credited Valentine with their conversion to Communism, which they saw as the only serious resistance against the fascism threatening Europe. Early in 1935 MI5 picked up on these new Party members (initially under the impression that Valentine was a man, and that Townsend and Warner were two different people). They were put under surveillance for possible ‘subversive activities’ or appearing ‘in any way abnormal’ – so there was plenty of scope. Surveillance reports detail Valentine’s ‘male clothing’, rabbit-shooting with a rifle and MG sports car driving, while admitting that Sylvia ‘appears normal in habits.’ Their intercepted post reveals an extraordinary level of routine party work, but nothing very illegal.

During the Spanish Civil War both writers volunteered for the British Red Cross in Barcelona, where Valentine did some ambulance-driving but even more impatient waiting. As delegates to a 1937 anti-fascist writers’ conference, they experienced the bombardment of besieged Madrid and the front line at Guadalajara. Valentine’s Daily Worker articles vividly evoke the spirit of the time, its idealism and brutality. Her investigative reporting on rural poverty was also published as a book, Country Conditions (1936).

Valentine was drinking heavily, and after 1935 she was often unfaithful to Sylvia, who initially tolerated Valentine’s ‘light loves’ (and even colluded, as her confidante). But when they attempted to recruit a wealthy American friend, Elizabeth Wade White, to the Party, an affair began which was not controllable like the others. Elizabeth was a person to be reckoned with, who had no intention of sharing Valentine. She persuaded them both to visit her in America, intending to keep Valentine there, but the timely outbreak of war meant that the unhappy affair was suspended when Valentine returned to Britain, with Sylvia.

They were now living at Frome Vauchurch, inland from Chaldon, in the secluded house on the riverbank where they remained for the rest of their lives. Valentine spent much of the war typing knitting-patterns in the Territorial Army HQ, blacklisted by MI5 as ‘not a person who should be employed on highly confidential work.’ Both the frustrations of her job and the horrors of the war frayed Valentine’s mental health, although she was still writing poems, including one of her best-known, Teaching to Shoot, which describes the collision of love and death as she shows Sylvia how to kill, in preparation for the expected Nazi invasion.

After the war, Valentine believed (at forty) she should relinquish physical love for the spiritual life. She embarked on a philosophical quest and, perhaps because of this, in 1947 her alcohol addiction mysteriously left her. But, when travel was again possible in 1949, Elizabeth reappeared, and the affair soon resumed. Sylvia was by now used to Valentine’s frequent casual unfaithfulness, but this was different; Elizabeth wanted to replace Sylvia, and almost succeeded. For a month, Sylvia actually moved out of the house at Frome Vauchurch while Elizabeth and Valentine lived there together; an experiment which predictably failed. (Elizabeth’s partner, Evelyn, was waiting for her, and Valentine had already realised it would be impossible to live without Sylvia.) After the painful end of the affair Valentine wrote ‘I feel myself destroyed.’

Remarkably, her relationship with Sylvia survived. Although the experience inevitably scarred them (and Elizabeth never entirely relinquished her claims), Valentine and Sylvia remained committed to their long partnership. They spent the winter of 1950-51 at Salthouse in Norfolk, living in an isolated folly on the shingle beach, alone together, writing, sometimes feeling ‘extreme happiness’. Sylvia recognised that Valentine was celebrating ‘a repossession of me, of our life and love together… a sense of homecoming to her undivided self.’

In 1952, still under surveillance by MI5, Valentine started a ‘small antiques’ business which, because of her good eye for idiosyncratic objects, thrived. Sylvia, too, enjoyed their buying-trips around the country and wrote stories inspired by the antiques. But Valentine’s inner life still focused on writing poetry, and although her work was published regularly in magazines, she was still disappointed by her relative lack of recognition, comparing her own modest output with Sylvia’s flourishing career. Sometimes she suspected that sobriety and abstinence had dried up her creativity.

Seeking new inspiration, Valentine re-joined the Catholic church in 1956, a gesture which appalled Sylvia. To her, it was a repudiation of their alternative life together, their loyalty to the Communist cause in Spain, even their Englishness. This ideological clash was ultimately more damaging to their mutual understanding than the affair with Elizabeth; it was a faith (or faithlessness) Sylvia could not comprehend or forgive. Ten years later, when the Latin mass was replaced with a vernacular liturgy she found ‘hopelessly unpoetic’, Valentine finally quit. She joined the Quakers, whose tradition of pacifism and socialism, non-hierarchical ethos and acceptance of gay relationships also appealed to Sylvia.

During the 1950’s and 60’s, Valentine wrote political poems protesting against ‘Vietnam or any of the other wars’, nuclear weapons, the inhumane treatment of refugees, Soviet dissidents and Greek political prisoners, the invasion of Tibet, and other human rights abuses. This political activism came at some personal cost; her world view became very dark, and she and Sylvia often disagreed about Stalin’s legacy (Sylvia insisted the horror-stories were anti-Red propaganda). Valentine’s pastoral poetry now lamented the increasing scale of environmental destruction, and she and Sylvia campaigned against a nuclear facility on wild heathland near Chaldon.

In early 1968, Valentine was diagnosed with breast cancer, and had an apparently successful operation. During that summer she and Sylvia stayed quietly at Frome Vauchurch, experiencing a renewal of their love, and a renewal of creativity for Valentine, who wrote some remarkable poems of mortality. By the autumn, she was obviously ill again, and underwent another operation. Before it Sylvia wrote to her: ‘that glorious span of thirty-eight years love and trust and happiness – courage and care too – will shine on us and protect us…’ and she was surprisingly right; now they felt ‘back in our glorified, glorious beginnings’ Valentine found that they ‘really were happy.’

Valentine died on 9 November 1969; she was sixty-three. Sylvia outlived her younger lover by almost nine years. Much of that time she spent remembering Valentine and memorialising their life together, grieving and writing. The epitaph from Horace which Valentine chose for their grave, Non omnis moriar (‘I shall not altogether die’), was certainly true for Sylvia as she re-read their diaries and letters. In these writings we catch a glimpse of the daily texture of their long life together; the damp riverine house smelling of Gauloise cigarettes, woodsmoke and garlic; the frequent drives through their beloved countryside to see bluebells or hear the sea; the seasonal rituals of gardening and cooking; the opening of books and wine-bottles; the radio playing classical music; the constant writing (by pen and ink or typewriter) of poetry, prose, diaries and many letters.

In the letter which Valentine called her most precious possession Sylvia wrote: ‘my heart’s thanks for all you have given me, all your understanding, your support, your tenderness, your courage, your trust… Never has any woman been so well and truly loved as I.’

Her tribute encapsulates the contradictions of the lover who could make Sylvia feel so uniquely loved while loving so many others, who was not exactly woman or man, who Sylvia claimed could be either Saint or Rogue. She’d been a Communist and a Catholic, an alcoholic and non-drinker, a fighter and pacifist, depressive and humourist, animal-lover and crack shot, a Londoner and a country-dweller, a wife and a husband – but always a poet. Ultimately, Valentine remains the ‘mysterious enchanted creature’ who never ceased to fascinate Sylvia.