Claire Harman

Sylvia Townsend Warner was born on 6 December 1893 at Harrow on the Hill in Middlesex, the only child of George Townsend Warner (1865-1916), a distinguished history teacher at Harrow School, and Nora Hudleston (1866-1950), the daughter of an Army family. Sylvia received no formal education after kindergarten age, but the private schooling she had from her father and other members of Harrow School’s staff more than compensated for that, while the personal and imaginative freedom she enjoyed as a young person helped form her marked individualism as a writer.

Music was Warner’s dominant interest in her teens, and she was intending to go abroad to study composition before the outbreak of war in 1914 put an end to that plan. During the early years of the war, she worked in a munitions factory and helped organise aid for Belgian refugees in Harrow, but the untimely death of her father in 1916 propelled her into an independent life as a scholar of music, and a move to London. For ten years, she was the only female member of the editorial committee of the Carnegie UK Trust’s Tudor Church Music project, a work of significant and lasting scholarly importance. Warner’s closest but most secretive relationship during this period was with another member of the committee, Percy Carter Buck, with whom she had begun an affair while he was still music master at Harrow School. Buck was married, and had five children.

In her first years in Bayswater, Warner’s circle of friends consisted mostly of old Harrovians, one of whom, the sculptor Stephen Tomlin, introduced her to members of the Bloomsbury Group and, more congenially to Warner, took her to meet the eccentric Dorset writer he had discovered and was championing, Theodore Francis Powys. Warner’s enthusiasm for Powys led to her becoming friends with his other strong promoter, the novelist David Garnett, and Garnett’s publisher, Charles Prentice, of Chatto & Windus; Prentice was quickly impressed by Sylvia’s poetry and published her first collection, The Espalier in 1925. A novel, Lolly Willowes, appeared the following year and was an immediate success; its mixture of fantasy and sharp wit was fresh and appealing, as was the slyly subversive story, which was of a single woman in the years just after the Great War who turns to witchcraft as the only practical way of asserting herself.

Though she continued working on the Tudor Church Music project until its completion, the success of Lolly Willowes encouraged Warner to become a full-time writer and two more novels followed in the next three years, as well as a further substantial collection of poetry, Time Importuned, a large amount of literary journalism and several novella-length stories. Among the plaudits she received in this busy period was to be chosen as the first ever ‘Book of the Month Club’ choice in the United States, being nominated for the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize and travelling to New York as a guest editor of the Herald Tribune. Critically, she was bracketed with writers such as Powys and Garnett, but she remained much more diverse than either of those writers, and unpredictable in her choice of subject matter; her lyrical novel of 1927, Mr Fortune’s Maggot, was the story of a missionary (‘fatally sodomitic’ as she described him later) who manages to lose his own faith rather than make converts among a group of South Sea Islanders, while The True Heart (1929) was a 19th-century retelling of the myth of Cupid and Psyche, with the Cupid character appearing as the simpleton son of a proud vicar’s wife.

Sylvia’s friendship with T.F.Powys made her a frequent visitor to his home in East Chaldon, and in 1930 she bought a cottage in the village. It was intended as a place of retreat from London, but when Sylvia fell in love with the poet Valentine Ackland, the couple made it their first Dorset home. With the exception of a short residence in Norfolk, they spent the rest of their lives in the county, moving in 1937 to a riverside house in Frome Vauchurch, Maiden Newton, about ten miles north west of Dorchester.

Valentine’s own career as a writer was just beginning when the two women met in the late 1920s and Sylvia was keen to advance it; however, an attempt to do so by publishing a joint collection of poems in 1934, called Whether a Dove or Seagull, misfired badly. The work of the two poets was mixed together and unattributed, but this provoked just the sort of speculation and pre-judgements which they had sought to avoid. The experiment distracted readers, while the frank lesbianism of some of the work may also have perturbed them; part of Ackland and Warner’s intention had been to celebrate their relationship, which they always referred to privately as a marriage.

The couple’s outsider status intensified when in 1935, on Valentine’s initiative, they became active and enthusiastic members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Their involvement in raising funds and writing party propaganda drew the attention of MI5, and they were under surveillance for almost twenty years as possibly dangerous subversives, a fact which would have pleased both women had they been aware of it. They travelled to Spain together twice during the Civil War, to Barcelona in 1936 to work with the Red Cross and as delegates to the International Writers’ Conference in Madrid in 1937; Sylvia made lasting friendships with fellow-minded writers during this time and retained an internationalist cast of mind and strongly left-wing sympathies all her life. She wrote two more novels in the thirties, both reflecting contemporary politics through the prism of the past, Summer Will Show (1936), a novel about the revolutions of 1848 and After the Death of Don Juan (1938), an allegory of the rise of fascism in Spain, based on the characters in Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

When the Second World War broke out, Sylvia became active in the local Womens’ Voluntary Services, helping to house refugees from the blitz in London, and lectured on history, literature and politics to the Workers’ Educational Association, the Labour Party and the troops. During the war, she began to write an ambitious and innovative novel about life in a medieval Norfolk nunnery called The Corner That Held Them, which was published in 1948; she was also writing short stories for the New Yorker, a connection which was to prove both lucrative and stimulating. Though Warner didn’t publish another novel after The Flint Anchor in 1954 (it was a complex family saga set in a Norfolk fishing town in the 1840s), the high profile of her New Yorker stories encouraged her to experiment, and it was the form she became best known for, culminating in the collections Winter in the Air (1955), A Stranger with a Bag (1961), The Innocent and the Guilty (1971) and her subversive moral fables Kingdoms of Elfin (1977).

The years following the war were extremely stressful for Warner personally, as Valentine had been conducting a long affair with a wealthy American writer, Elizabeth Wade White, which reached a crisis in 1949. The marriage survived, but was shaken; further difficulties arose when Valentine left the Communist party in the 1950s and became a Roman Catholic, much to the horror of her atheist partner. Valentine’s poetry and her intellectual pursuits remained central to her life; she also wrote short fiction, social commentary and a startling memoir that was published posthumously under the title For Sylvia (1985). But the couple’s last years together were clouded by the onset of illness and when Valentine died of breast cancer in 1969, Sylvia’s bereavement was profound and long-lasting, recorded in unpublished poems and in heartbreakingly eloquent diaries. As a way to recall and memorialise their relationship, she ordered and annotated the many hundreds of letters the two women had written to each other over thirty nine years, which, published posthumously in 1998 as I’ll Stand By You, constitute an extraordinary and profoundly moving love story.

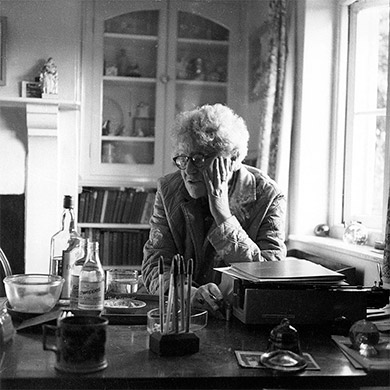

In the last decade of Sylvia’s life, there was a revival of interest in her work and several of her novels were republished under new feminist imprints, but she remained a somewhat ghostly and marginal presence in the English literary landscape. Her originality and detachment, as well as her gender, sexuality and politics, had tended to keep her outside the canon; the scope of her interests and versatility were also perhaps hard for her contemporaries to categorise or digest. As well as being a superlative writer of fiction and poetry, Warner was a perceptive critic and editor, producing a short study of Jane Austen (1951), a highly-praised biography of the writer T.H.White (1967), a guide to Somerset (1949), Portrait of a Tortoise (1946 – about the naturalist Gilbert White’s tortoise, Timothy) and the first English translation of Marcel Proust’s Contre Sainte-Beuve (1958).

In the years since her death on 1 May, 1978, an even fuller picture of her remarkable abilities and achievements has emerged with the publication of her Collected Poems (1982 and 2008), a selection of Letters (1982), Selected Stories (1988), Diaries (1994) and selected prose writings With the Hunted (2012), as well as books dealing with individual correspondences, such as Sylvia and David: The Townsend Warner/Garnett Letters (1994) and The Element of Lavishness (2003). Scholarship and commentary on her work has burgeoned in the past twenty years, appreciation of her subversive wit and captivating personality has spread and in 2021 all her novels will be in print simultaneously for the first time (as Penguin Modern Classics). Belatedly but firmly, Warner is assuming her rightful place in the narrative of twentieth century English letters.